#comptes rendus des séances de l'académie des sciences

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

via Gridllr.com — view & reblog all your Likes!

Urbain-Jean-Joseph Le Verrier, Sur la planète Neptune, «Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des sciences», Volume XXVII, September 11, 1848, Institut de France, Académie des sciences, [ca. 1850], pp. 1-8 [Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris]

#graphic design#astronomy#mathematics#journal#urbain le verrier#comptes rendus des séances de l'académie des sciences#bibliothèque nationale de france#académie des sciences#1840s#1850s#Urbain-Jean-Joseph Le Verrier#Sur la planète Neptune#«Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des sciences»#Volume XXVII#September 11#1848

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not a new academic journal article about Paul Gavarni, but newly found by me: "Parisian Social Statistics: Gavarni, 'Le Diable à Paris,' and Early Realism" by Aaron Sheon (Google Drive link). I think this will be of interest to many of my friends here—

Le Diable à Paris is important to art historians because it included a series of illustrations by Guillaume Sulpice Chevallier, known as Gavarni, the popular Parisian illustrator who was one of the city's most colorful personalities—a bohemian and flaneur. His entire series of illustrations showing types of Parisians, particularly the poorest ones, was popular enough to be later assembled as Les gens de Paris in a separate book. Each illustration was captioned by Gavarni himself, who took pride in writing a touching or witty description for each image.

Gavarni's illustrations in Le Diable à Paris included some of the cruelest scenes of waifs, paupers, beggars, and les misérables that had yet been done. It is surprising that they have been overlooked in recent studies of the politicization of French artists in the 1840s. The curious neglect of his imagery of the destitute, unemployed Parisians in Les gens de Paris appears to be due to the general neglect of Gavarni's oeuvre. When considered at all, Gavarni has been viewed by most historians as a conservative artist, a gay blade who lived only for carnavals and bohemian self-indulgence. This assumption may be incorrect.

This is a really, really, really good article about Gavarni's world, probably the best source I've found next to his biography by Jules and Edmond de Goncourt (which is in French). There is some fascinating background on the gathering of social data and the development of the modern statistical bureau in early 19th century France; and the content of Le Diable à Paris is a LOT darker and more socially conscious than I imagined. I had thought that it was a more light-hearted work before Masques et Visages but definitely not. (Which makes it even more inexplicable that people in 1840s Britain thought that Gavarni was just a dandy who made elegant fashion drawings, only to be disappointed by his more complicated reality).

Very interesting information about provincial peasants flocking to 19th century Paris, where they lived in slums and faced discrimination and mockery for their regional dress and accents: "In the 1840s a number of pejorative words began to appear in novels and articles describing the immigrants: misérables, wretches, barbarians, savages, indigents, illiterates, nomads, vagabonds, and vagrants. Some writers described them as the 'mob' and a 'nation within the nation.'"

Special to @sanguinarysanguinity: I have FINALLY found some of Gavarni's mathematical work, thanks to this article! "Des fonctions curvitales" in Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences (1865). It's in French but maybe the equations will give you some idea?

Gavarni's publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel was a lot younger than I imagined! I had no idea Hetzel was a political activist in the 1830s and 1840s (and opposed to the regime of Louis Philippe). He signed Honoré de Balzac to a publishing contract, too! Note to self for the upteenth time: I have to start reading Honoré de Balzac, who is constantly being brought up in association with/compared with Gavarni.

Sheon puts a pretty good case together that Gavarni should be regarded as more politically progressive and less shallow, although it makes me ponder how little I know about him. Gavarni is still enigmatic to me, and I have so many questions.

#paul gavarni#french history#1840s#les misérables#but not the novel#july monarchy#early victorian era#sheon gets bonus points for getting gavarni's birth name correct#(i wish that was less rare)#why are my favourite historical figures always obscure and neglected#also mister gavarni i'm sorry i am so bad at reading french i don't properly appreciate your touching and witty captions :(

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Triadobatrachus massinoti

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Triassic frog

First Described By: Piveteau, 1936

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Temnospondyli, Euskelia, Dissorophoidea, Xerodromes, Amphibamiformes, Lissamphibia, Batrachia, Salientia, Triadobatrachidae

Referred Species: T. massinoti

Status: Extinct

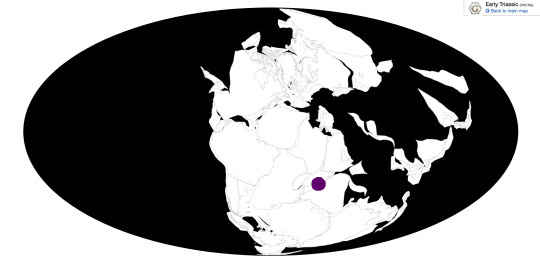

Time and Place: Approximately 251–250 million years ago, in the late Induan to early Olenekian of the Early Triassic.

Triadobatrachus is only known from the Sakamena Formation in Northern Madagascar.

Physical Description: Triadobatrachus superficially resembles modern frogs, it was only around 10 cm long, had a broad head and a very reduced tail. Its skeleton had many features associated only with frogs among amphibians, including a very frog-like skull with big eyes and their characteristically elongated hips. Soft tissues preserved around the fossil even show that it had the wide, round body of frogs too. However, the skeleton of Triadobatrachus differed from living frogs in a few major ways. It had much more vertebrae than living frogs, 26 compared to the maximum 4–9 of frogs alive today, giving it a much longer body, and these vertebrae had ribs, unlike living frogs. Its legs were shorter and more squat, especially its back legs, which were hardly any longer than its front ones, making Triadobatrachus incapable of hopping despite its derived hips. Even the stumpy tail was still more prominent than in living frogs, and may have even retained some degree of mobility. To sum it up, Triadobatrachus more or less looked like a stretched out frog with short legs. Think of a horned toad lizard but with more of the toad part and less horned.

Diet: Like other frogs, Triadobatrachus was probably carnivorous, likely feeding on invertebrates like insects and other arthropods, molluscs, worms, and perhaps even any small vertebrates it could fit in its mouth.

Behavior: One of the most standout features of Triadobatrachus is that it couldn’t have hopped like modern frogs. Instead, Triadobatrachus would have walked around on land more like a salamander, although it is unknown just how much time it would have spent on land in the first place anyway. It was clearly amphibious, and it probably swam by kicking its back legs like frogs, unlike the undulation of newts and salamanders. It would have spawned like living amphibians too, laying shell-less eggs in water that hatched into tadpoles and underwent metamorphosis just like modern frogs. Otherwise, its behaviour is a mystery. We don’t even know if it would have croaked or not.

Ecosystem: Not much is directly known about the ecosystem Triadobatrachus inhabited, as the only known fossil had been washed out to sea along the coast. The intact body at least implies the body wasn’t transported far, so Triadobatrachus probably lived in coastal floodplain rivers and swamps. Various other temnospondyl amphibians are known from the area, including Edingeralla, Deltacephalus, Mahavisaurus, Wantzsosaurus and Tertremoides. Despite being amphibians, many of these temnospondyls were likely euryhaline, meaning they could tolerate salt water and inhabited the coastline, something only a few living amphibians are even remotely capable of standing. The peculiar aquatic reptile Hovasaurus lived along the coasts, although it’s unknown if it ever crossed paths with the freshwater frogs, and terrestrial procolophonid parareptiles were also present. Plant remains suggest the environment was tropical and semi-arid with a monsoonal climate that supported conifer forests along with seed ferns, horsetails and clubmosses.

Other: Triadobatrachus is one of the only known stem-frogs, along with the polish Czatkobatrachus, and is certainly the oldest. The early evolution of Lissamphibia (all living amphibians) is poorly understood, particularly whether their ancestry lies in the temnospondyls or some other “amphibians”. Triadobatrachus doesn’t solve this debate, although it does show similarities to the Permian amphibamiforms like Gerobatrachus, supporting the temnospondyl affinity for batrachians (the frogs and salamanders) amongst dissorophoids.

Before they were considered to be temnospondyls, lissamphibians were often thought to be lepospondyls, a probably paraphyletic or even polyphyletic (i.e. unnatural) collection of “amphibians” on the tetrapod tree more derived than temnospondyls (some may even be honest to goodness amniotes!). This picture is complicated by caecilians, which at one point were suggested to be lepospondyls while batrachians were temnospondyls, making Lissamphibia polyphyletic! The story got even stranger after a little Triassic amphibian, Chinlestegophis, was discovered in 2017 and was considered to be a stem-caecilian. Chinlestegophis pulled caecilians back into temnospondyls with the other lissamphibians, but at almost opposite ends of the temnospondyl tree—batrachians in amphibamiforms and caecilians in with the stereospondyls related to the giant metoposaurs! So lissamphibians may all be temnospondyls...but also polyphyletic, unless nearly all of Temnospondyli is classed as lissamphibians and becomes part of the crown group. This would also mean our small modern amphibians both independently miniaturised from the much larger, classic predatory amphibians of the Palaeozoic and Triassic. What a concept.

Regardless of temnospondyl taxonomic troubles, Triadobatrachus is a perfect transitional form from more generalised amphibians to the highly specialised anatomy of frogs. Particularly, it shows that some of their unique anatomical adaptations evolved before they were able to hop, and may have functioned for other activities like swimming. The almost complete preservation of a skeleton as delicate as one of a small amphibian is a remarkable find, let alone one that represents a perfect transitional form for a group of animals whose evolutionary history is shrouded in mystery, and makes Triadobatrachus a fantastic find, no matter how unassuming it may be.

~ By Scott Reid

Sources under the Cut

Ascarrunz, Eduardo; Rage, Jean-Claude; Legreneur, Pierre; Laurin, Michel (2016). "Triadobatrachus massinoti, the earliest known lissamphibian (Vertebrata: Tetrapoda) re-examined by µCT-Scan, and the evolution of trunk length in batrachians". Contributions to Zoology. 58 (2): 201–234.

Lires, A. I., Soto, I. M., & Gómez, R. O. (2016). Walk before you jump: new insights on early frog locomotion from the oldest known salientian. Paleobiology, 42(4), 612-623.

Maganuco, S., Steyer, J.S., Pasini, G., Boulay, M., Lorrain, S., Bénéteau, A., Auditore, M. (2009). “An exquisite specimen of Edingerella madagascarensis (Temnospondyli) from the Lower Triassic of NW Madagascar; cranial anatomy, phylogeny, and restorations”. Società italiana di scienze naturali.

Pardo, Jason D.; Small, Bryan J.; Huttenlocker, Adam K. (2017-07-03). "Stem caecilian from the Triassic of Colorado sheds light on the origins of Lissamphibia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (27): E5389–E5395

Piveteau, J. (1936). "Une forme ancestrale des amphibiens anoures dans le Trias inférieur de Madagascar". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences. 202: 1607–1608.

Rage,J-C; Roček, Z. (1989). "Redescription of Triadobatrachus massinoti (Piveteau, 1936) an anuran amphibian from the Early Triassic". Palaeontographica Abteilung A. 206: 1–16.

Roček , Z., Rage, J-C. (2000). "13. Proanuran Stages (Triadobatrachus, Czatkobatrachus)". In Heatwole, H.; Carroll, R. L. (eds.). Amphibian Biology. Paleontology: The Evolutionary History of Amphibians. 4. Surrey Beatty & Sons. pp. 1284–1294.

Ročková, H., Roček Z. (2005). “Development of the pelvis and posterior part of the vertebral column in the Anura”. Journal of Anatomy. 206(1): 17–35.

Xing, L., Stanley, E. L., Bai, M., & Blackburn, D. C. (2018). “The earliest direct evidence of frogs in wet tropical forests from Cretaceous Burmese amber”. Scientific reports, 8(1), 8770.

#Triadobatrachus#Triadobatrachus massinoti#Frog#Palaeoblr#Triassic Madness#Triassic March Madness#Triassic#Prehistory#Paleontology#Prehistoric life

157 notes

·

View notes